José Vasconcelos

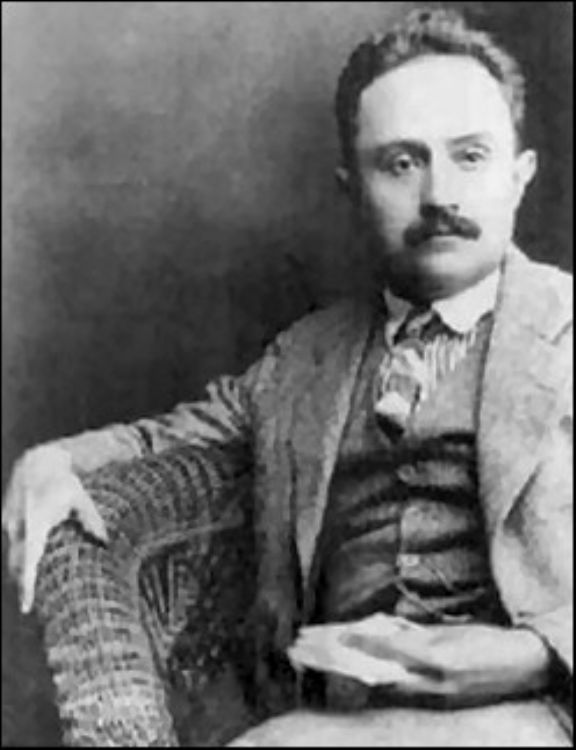

José María Albino Vasconcelos Calderón was born in Oaxaca on February 28, 1882. The second of nine siblings, he spent his childhood in the states of Coahuila, Sonora and Campeche due to his fatherâs work in customs. Vasconcelos was a renowned lawyer, politician, writer, educator, public official and philosopher of Mexico.

In 1907 he graduated in Law. Only two years after having completed his studies, together with other intellectuals of his era, he founded and was president of Ateneo de la Juventud, in 1909. Ateneo was formed by Mexicans who criticized the excesses in education imposed by Justo Sierra, minister of Public instruction during the government of Porfirio Diaz. With a great quality of criticism, Vasconcelos and the Ateneoâs generation proposed a wider perspective in education and rejected the biological determinism that was used to justify racism. They requested freedom to teach, freedom of speech and to reaffirm the cultural, ethical and esthetical values of Latin America; this was prompted by the characteristic of Porfirio Diaz to be fascinated by everything European. With this, the Ateneoâs generation set the bases to recover the Mexican and Latin American culture as an identity for sustained progress.

He participated in the Mexican Revolution by invitation of Francisco I. Madero. In 1920, Vasconcelos became affiliated with Alvaro Obregón against Venustiano Carranza and after the death of the latter, interim president Adolfo de la Huerta named Vasconcelos Minister of Education, a post that included being the rector of Universidad Nacional de Mexico (UNAM) from 1921 to 1924. During that time, he proposed the motto of the emblem that is still preserved: âPor mi Raza Hablará el Espírituâ (the spirit will speak through my race), referring to the conviction expressed in his famous speech: âI am not here to work for the University, but to ask the University to work for the peopleâ.

Vasconcelos began an ambitious project of cultural promotion throughout the country with programs of popular instruction, book editions and the promotion of arts and culture. His goal was to integrate Mexico into the great transformations that followed the First World War. Vasconcelos transformed each rural teacher into an âeducation apostleâ, according to his catholic roots, inspired by the sacrifice of missionaries during the colonial era. To support this project, he began a massive edition, called Misiones Culturales of the greatest works of universal ideas and distributed it all over the country.

He also supported many intellectuals and artists, creating with them formulas of massive artistic expression. He was joined by great personalities such as David Alfaro Siqueiros, José Clemente Orozco, Diego Rivera and Gabriela Mistral.

Another aspect of his tireless work was the construction and reconstruction of public buildings for cultural promotion such as public schools and libraries.

Worried about the policies of then President Plutarco Elias Calles, in 1929 Vasconcelos decided to become a presidential candidate, in opposition to the candidate of Calles, Pascual Ortiz Rubio. Supported by some of the greatest intellectuals and artists of that era, he developed an ambitious campaign that built the hopes of many but he wasnât elected. His followers denounced electoral fraud and Vasconcelos proclaimed the Plan of Guaymas, calling for an uprising in an attempt to imitate the revolution began by Madero twenty years before. Imprisoned for this, he named himself âthe only legitimate authorityâ and refused to recognize federal, state and municipal authorities. The insurrection didnât have any followers because society was tired after ten years of civil wars (Mexican Revolution and Cristero War). After being freed, Vasconcelos began a productive exile through the United States and Europe, where he was completely dedicated to philosophical analysis and writing his monumental autobiography.

In 1940 he returned to Mexico as director of the National Library, university professor and creator of controversy. He was named Doctor Honoris Causa by UNAM and the National Universities of Puerto Rico, Chile, Guatemala and El Salvador. He was a member of Colegio Nacional and the Academia Mexicana de la Lengua.

Prolific writer, he published a series of autobiographical novels portraying details of the Porfiriatoâs disintegration, the development of the Mexican Revolution and the post-revolutionary regime. His vast literary work includes nearly fifty essays and books on Law, Philosophy, History of Mexico, Metaphysics, Ethics, Sociology and general culture. His most famous work is a book that has formed the political ideas of Latin America: La Raza Cósmica (1925), where he strongly criticizes the racism that since XVI has attempted to justify the submission of Latin America under Europe and the United States.

He died in the neighborhood of Tacubaya in Mexico City, on June 30, 1959.

Artículo Producido por el Equipo Editorial Explorando México.

Copyright Explorando México, Todos los Derechos Reservados.

Foto Portada: Wikipedia.org