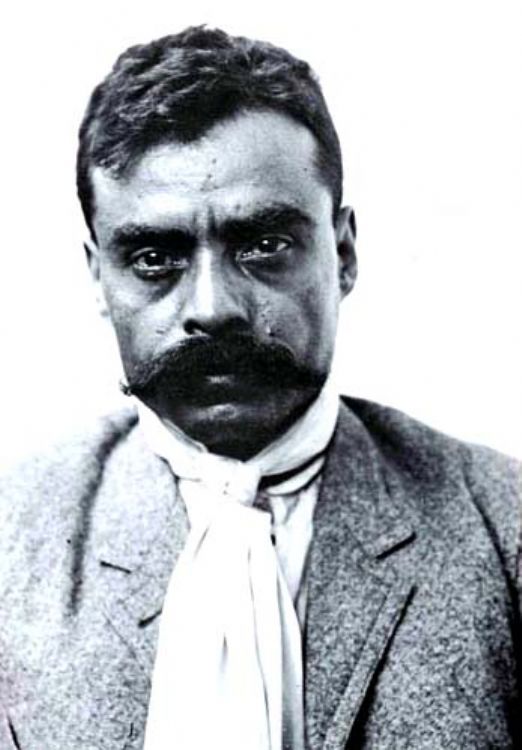

Pancho Villa

Pancho Villa, an icon of the Mexican Revolution, was born in San Juan del Río, Durango, on June 5, 1878. Baptized as Doroteo Arango, he suffered a peasantâÂÂs life and witnessed how the rich landowners amassed great fortunes by exploiting workers. His father died when he was only 15 years old, forcing him to work full time in order to support his mother and four siblings. In 1894, he killed his boss while defending his sister from sexual abuse and was forced to flee. From 1894 to 1910, he lived as a fugitive and was rescued by bandits led by a man named Francisco Villa, who soon recognized his loyalty and courage, assigning him as leader of the gang while he lay agonizing from a gunshot wound. Arango took control of the band and his mentorâÂÂs name.

This is how his acts of rebelliousness and vandalism started to develop. Enraged by the workersâ misery, he assassinated many landowners and robbed trains, livestock and mines to care and feed the less fortunate. He soon became known throughout the country as The Friend of the Poor.

His voraciousness as bandit and ability to keep avoid being captured, caught the attention of those who planned the revolution, to act as a guerilla leader. In 1910, Francisco I. Madero defied Dictator Porfirio Diaz with a program of social reforms and called for the insurrection. Villa joined his cause and put his improvised troops in service of the Revolution. In 1911, Madero managed to overthrow Porfirio Diaz and was elected president, turning Villa into an army general to fight against the powerful private groups who refused to distribute land among the workers. However, Villa gave up this post because he didnâÂÂt agree with a fellow commander, Pascual Orozco.

On May 29, 1911, Villa married Maria Luz Corral and tried settling down into a peaceful life, but the countryâÂÂs political unrest prompted him to fight alongside General Victoriano Huerta in support of Francisco I. Madero, who was being attacked by Orozco. Huerta didnâÂÂt approve of his new ally, accused Villa of insubordination and ordered his execution. VillaâÂÂs life was pardoned by Madero but put in jail. Villa was imprisoned from June to December 1912, when he fled from the military prison. Madero didnâÂÂt order the recapture of Villa, probably because he was convinced of his innocence.

In February 1913, Huerta murdered Madero and usurped the presidency, forcing Villa to join Venustiano Carranza against him. Pancho Villa fought many successful battles during the following years, conquering vast areas in the north to stabilize economy and justice. With an army of peasants, Villa conquered Chihuahua in late 1913 and led the famous Northern Division, capturing Ciudad Juarez in November 1913, Ojinaga in 1914 and winning the epic battle of Torreon in March 1914. The Northern Division campaign against the regime of Huerta ended with the fall of Zacatecas on June 24, 1914. In the summer of 1914, Villa and Carranza parted ways, reigniting the ongoing civil war.

United States supported Carranza and in 1916, Villa attacked Columbus, New Mexico, as the first attack on North American soil since 1812. The U.S. government sent a few thousand soldiers along the border to capture Villa and even though they spent over a year searching, they never found him.

In May 1920, Carranza was murdered and Adolfo de la Huerta became interim president; he negotiated with Villa to quit the cause, offering the Canutillo Estate in Chihuahua as part of the peace agreement. This prompted Villa to give up his weapons in June 1920, at Sabinas in Coahuila, promising to interfere no further in the countryâÂÂs politics.

Pancho Villa lived peacefully during the next three years, but when the next presidential elections were coming near, the great revolutionary leader decided to test his popularity. His charisma was enough to raise a few thousand men against the government and even though he was not interested in any political post, he wanted to keep having influence over national issues, as evidenced by the growing interest of national and international media.

Even though Villa was loved by many, he was also hated by others who wanted revenge. Congressman Jesus Salas Barraza and powerful businessman Gabriel Chavez, were obsessed with eliminating Villa for personal reasons. President Obregon and future presidential candidate, Plutarco Elias Calles, became aware of the plot against him and did nothing to avoid it, Calles even guaranteed impunity for the future assassins.

The assassins chose Parral for the ambush, an old mining town in Chihuahua that Villa used to visit often to meet with one of his many love interests, Manuela Casas. This townâÂÂs layout forced all cars to drive through Plaza Juarez, in front of which the assassins rented a room. Pancho Villa and his personal secretary, Miguel Trillo, prepared for the trip back to Canutillo on June 20, 1923. Four shooters stationed themselves on the window of the room and shot hundreds of bullets against VillaâÂÂs car as he was driving by, then they mounted their horses and fled.

Obregon and Calles pretended to be surprised by the crime and ordered a thorough investigation. Jesus Salas Barraza and Meliton Lozoya, two of the assassins, were apprehended, judged and sentenced to seventy years in prison, but were pardoned and let free only a year later.

Controversy followed Villa even after his death. In February 1926, his tomb was desecrated and his skull robbed. Myths soon arose in an attempt to explain this odd crime. One of the most peculiar is that North Americans, perplexed by his invasion of Columbus in 1916, decided to study VillaâÂÂs brain and the other states that Coronel Francisco Durazo, chief of the Parral Garnish, read about a 50 thousand dollar ransom on VillaâÂÂs head and interpreted it literally. For whatever the reason, his head has never been found and his corpse rests within the Revolution Monument in Mexico City.

Article Produced by the Editorial Team of Explorando México.

Copyright Explorando México, All Rights Reserved.

Photo: www.schema-root.org