The Cristero War

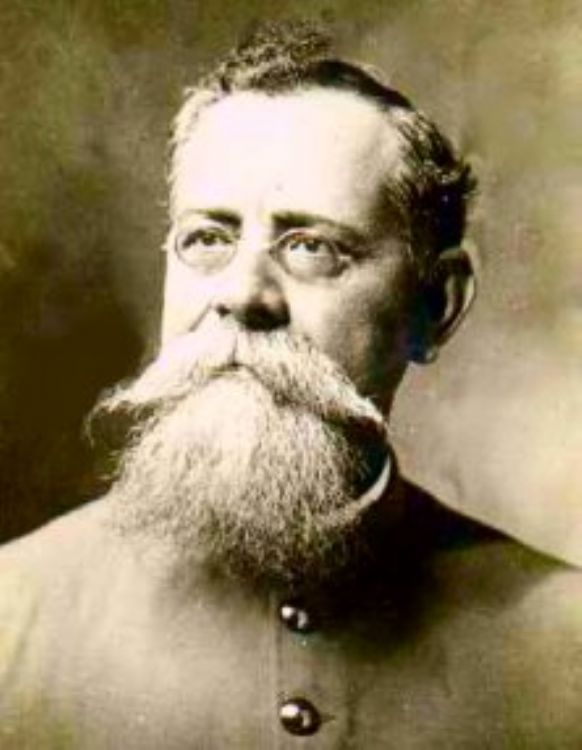

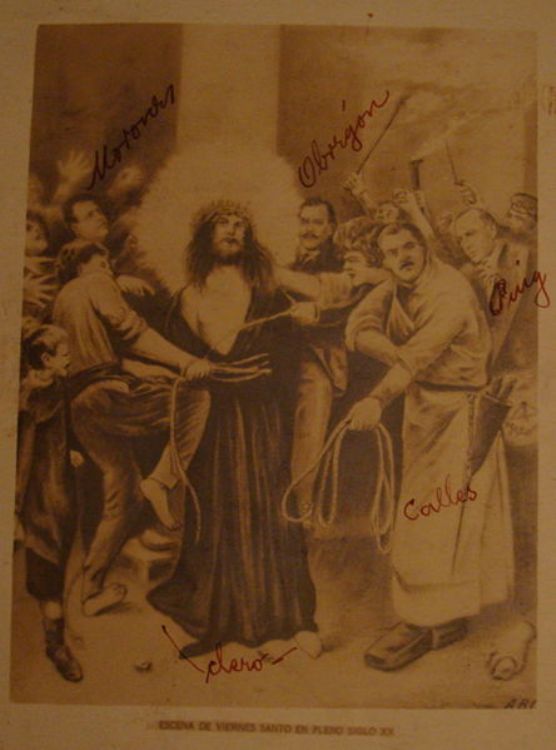

The Cristero War is also known as Cristiada. It was an armed struggle between the Government and the Church from 1926 to 1929. If was fought between the administration of Plutarco Elias Calles and militias of secular, presbyter and religious Catholics that were against the public policies designed to restrict the autonomy of the Catholic Church. It is estimated that 250 thousand persons died, including citizens and soldiers.

In 1917 a new Constitution was promulgated, establishing a policy of religious intolerance, including the prohibition for the Church to own real estate, the prohibition of public cult outside churches, the State would decide the number of churches and priests in the country, the clergy was denied the right to vote, religious press was not allowed to refer to public issues, elementary school had to be secular and the religious corporations and ministers of cult were prohibited to establish or manage elementary schools.

In 1926, President Plutarco Elias Calles promoted instruments on article 130 of the Constitution to exercise severe control, searching to limit or suppress the participation of churches in public life. Some of these rules were clearly focused against Catholics, such as obligating the ministers to marry and prohibiting religious communities.

As a sign of mourning, many churches in the country suspended cult and the clergy convinced parishioners to boycott the government, such as to not paying taxes, to minimize the purchase of products sold by the government, to not buy lottery tickets and to not use vehicles in order to not buy gasoline. This severely affected national economy and inspired the radicalization of some groups among Mexican Catholics.

Catholic citizens formed the National League for the Defense of Religious Freedom in March 1925. Their goal was to achieve freedom of cult by legal means, but it was declared illegal and thus became an underground movement.

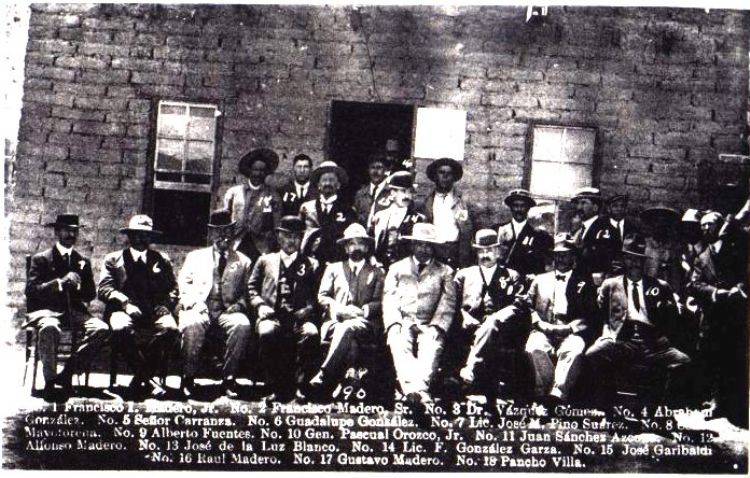

This radicalization grew as a social movement with the goal of vindicating the rights of worship in Mexico. This movement believed in reaching a solution through and armed conflict and was independent from bishops. In January 1927, the first guerillas, formed by farmers, began to gather weapons. These armed forces were known as cristeros and grew by proclaiming Long Live Cristo Rey! and Long Live Santa María de Guadalupe! An efficient way to add followers to the cause was the use of symbols profoundly rooted in Mexican culture, such as the Virgin of Guadalupe, formerly used with the same goal by leaders of the Independence and Revolution struggles.

The states where they first started to revolt were Jalisco, Zacatecas, Guanajuato and Michoacan, but soon the whole central part of the country had joined. It is estimated that by 1929 there were 20,000 members in the cristero forces. Mexican bishops quickly attempted to distance themselves from the armed movement and tried to negotiate peace by requesting the government of United States to act as a mediator.

The underground character of the cristeros stopped them from having formal mechanisms for supplies, recruitment, training and medical attention; they could only depend on outdated weapons, the surplus from the Revolution of 1910.

This uprising created a grave rupture between the members of the National League for the Defense of Religious Freedom and Mexican bishops, whose reaction was to greater centralize and control the catholics through the newly created Mexican Catholic Action. A long negotiation began, serving as mediator the ambassador of Untied Stated in Mexico, Dwight Morrow. An agreement was reached granting general amnesty for all the cristeros who chose to give up. Approximate numbers state that only 14 thousand persons gave up their weapons, from among the 50 thousand persons involved.

Pope Pius XI reacted by publishing encyclicals that criticized the governments of Mexico, Nazi Germany and Italia for their anti-catholic policies.

The president of Mexico announced that the Catholic Church would submit to the law but in reality ânicodemic relationshipsâ were applied (referring to Nicodemus, the Pharisee that would approach Jesus during the night). In the practice, the State resigned from applying the law and the Church resigned from publicly disputing the imposed conditions. Mexicoâs archbishop became the only negotiator allowed to speak to federal authorities; the countryâs bishops would not make any more comments regarding national politics.

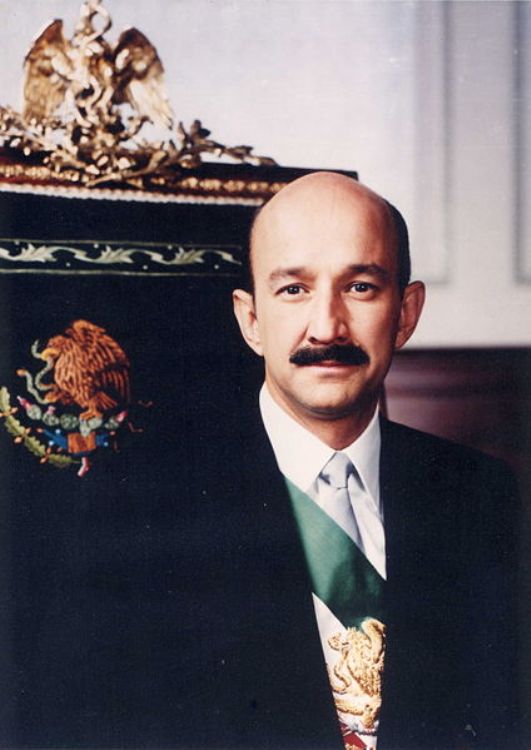

This is how the State-Church situation continued in Mexico until 1992, when then president Carlos Salinas de Gortari renewed diplomatic relations with the Vatican and promulgated a new law of cult. Congress reformed article 130 of the Constitution, granting legal presence to the Church.

Artículo Producido por el Equipo Editorial Explorando México.

Copyright Explorando México, Todos los Derechos Reservados.

Foto: Wikipedia.org